Many children are affected by congenital cardiovascular diseases and congenital heart defects are the leading cause of death in neonates. Almost one percent of children are affected by some sort of congenital heart defect and almost twenty-give percent of these patients require surgery.

Many congenital hear defects involve issues with arteries or veins and can result in a disruption of blood flow throughout the heart, so may require a bypass for the blockage or the replacement of a defective vein/artery.

Some patients get varying forms of transplants. Autografts, or the use of tissue from elsewhere in the patient, can be limited due to availability and quality of that tissue for transplant. Allografts, or tissue from a human donor, is limited due to a lack of donors and are immunogenic. Xenografts, or tissue from another species, is also immunogenic and may not necessarily be an effective replacement depending on the tissue.

Therefore, there is a need for the creation of therapies that do not require transplantation of tissue. One potential treatment are synthetic grafts made out of materials like PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) that exhibit adequate mechanical strength, but are non-biodegradable and exhibit poor integration of endothelial cells. Smaller diameter grafts are also likely to develop thrombosis (blood clots), stenosis, and become infected. An additional challenge experienced in pediatric and neonatal patient populations is the inability of synthetic graft materials to grow with the patient, making them a non-ideal solution for treating some of these congenital heart defects1.

The paper “Tissue engineered vascular grafts for pediatric cardiac surgery” discusses the results of a clinical trial by their group on tissue engineered vascular grafts (TEVG) for children with congenital heart defects. TEVG were made from biodegradable polymers, PCL and PLLA mixed with PGA or PLA that were seeded with cells. Follow-up data from a clinical trail conducted from 2001-2004 is presented on patients who received these TEVG. These biodegradable TEVGs in patients ranging from one year to young adulthood resulted in no graft-related mortality. Additionally, at 4 years post-implantation, there was no significant evidence of graft rupture, aneurysms, or calcification.

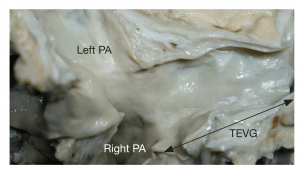

Image: An example of a tissue engineered vascular graft for implantation.

Many of the implanted TEVGs also demonstrated growth with the child. 6 of 25 patients had vessel narrowing of which 4 had balloon angioplasty and 1 had a stent insertion. The team is currently investigating causes of graft stenosis and ways to prevent this. However, the majority of the treated patients exhibit TEVG growth and remodeling, marking an improvement over synthetic grafts, at least in terms of applicability to pediatric and neonatal patients.

Image: TEVG 13 years after implantation with appearance similar to that of the native veins.

Based on properties of TEVGs that we expect, there may also be a decreased inflammatory or immunogenic response and a decreased risk of dilation, although this was not explicitly discussed or analyzed within the paper.

This paper is a good start towards providing evidence that TEVGs may be an improvement over other current clinical treatments. Since this is done with a relatively small sample size as a Phase One clinical trail in pediatric patients, further expansion of the sample size is needed. Adverse effects may occur at lower frequencies that are not observed with a small sample size.

Additionally, given the success of this group in treating pediatric patients, a similar study for neonates should be conducted. Children as young as one year were included in this clinical trial and the majority of patients were under the age of five. Therefore, given its success in very young children, this technology as currently created may hold great promise in treating neonates.

Another interesting direction to investigate is whether faster TEVG remodeling and cellular integration from the patient would occur if particular ECM molecules were added in varying ratios. Collagen, elastin, and gelatin are all common ECM components and have been used for TEVGs as a “collagen gel approach.” Integrating some of these molecules into this TEVG in varying ratios could result in better biocompatibility and decreased adverse events.

References:

Shoji, T. et. al. Tissue engineered vascular grafts for pediatric cardiac surgery. Translational Pediatrics (2018). 7(2): 188-195.