This guest post is by Connor Williams, a second-year graduate student in the Yale History Department, who has been working as a graduate assistant on a project in Manuscripts and Archives to identify more collection materials relating to slavery, abolition, and resistance in the 19th-century United States.

I had great hopes for the William and George, the Woolsey brothers. At first glance, their resumes seemed impeccable: they were New York merchants who at times served as presidents of both the New York Chamber of Commerce and the New York Manumission Society. William also fathered Theodore Dwight Woolsey, Yale’s anti-slavery President during and after the Civil War, and through his service their surname graces Yale’s grand concert hall and war memorial, where the walls bear the names of the 114 Yale men who died for the Union. (For full disclosure, 54 Yalies also died for the Confederacy, and their names are intertwined alphabetically with their Yankee classmates, providing a troubling reminder of how far the Lost Cause spread). On more esoteric matters the Woolseys also appealed to my northeastern biases—they were early blockade runners when Jefferson forced his myopic Embargo Act upon the merchant classes, and savvy operators in international trade. William even petitioned that Congress include black and foreign-born seamen in its 1795 act guarding against sailors’ impressments, acknowledging that though not U.S. citizens, they nonetheless sailed for American merchants and deserved “the protection of the American flag.” Taken in sum, the Woolseys presented that which so often eludes a student of the New Republic and the 19th century: pro-union, anti-slavery federalists who were civic minded and strove to enhance the lives of many. In short, some early Americans who we can celebrate without reserve, and in whose eponymous concert hall the Yale Glee Club can perform without regret.

Yet maxims exist for a reason: and that which seems too good to be true almost always is. Reading through the Woolsey’s business records, slight patterns start to emerge. Though noble in purpose, the manumission society’s practices leave something to be desired for the modern researcher: one manumission was contingent on the slave’s faithful service as a deckhand aboard two dangerous voyages to the East Indies and back, while another master manumitted his slave only after the slave finished eleven years service as a hired hand (the master received the wages). That man, twenty-seven years old at the time, would not receive his freedom until close to his fortieth birthday. A similar document, for a five-year-old girl whose owner calls her a “wench,” withholds freedom for twenty years.

In matters of trade, some troubling anecdotes also appear: most notably, in the summer of 1796, William Woolsey seemed reluctant to investigate claims that New York merchants were bringing enslaved men and women to Cuba in order to take away the valuable sugar products being created there. Despite being reminded that it was “a crime against humanity and the law of the United States” by a petitioner and receiving evidence of nine New York vessels plying the illicit trade, Woolsey only lukewarmly consented to form a committee to investigate future claims, and to act only if “any cases should be discovered sufficiently clear so as to warrant them to commence a suit.”

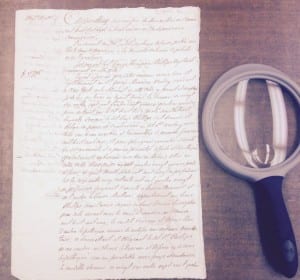

One of three plantation mortgages the Woolseys underwrote soon after the Louisiana Purchase. As with many documents issued in New Orleans, the text is entirely in French. Woolsey Family Papers (MS 562), Box 69, Folder 26.

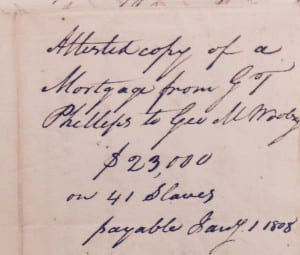

Perhaps Woolsey’s reluctance to investigate New York’s commercial ties to slavery was prophetic: seven years later the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory from France, and the Woolseys were some of the first major investors in the plantation products—especially cotton and sugar—that New Orleans now offered the nation. In 1805 George Woolsey even went so far as to employ New Orleans denizen George Phillips as his agent in the port to buy and ship slave-grown sugar and cotton up north: William signed on as a silent partner. From the start Phillips’ letters to Wolsey indicate an ambition that borders on avarice: he repeatedly asks for more buying power, fewer restraints on his agency, and more money. This process culminated in Phillips’ entry into three mortgages with the Woolseys for $75,000—at least $1,500,000 in today’s dollars, and almost certainly more in real value—to expand his New Orleans operation. For one of the mortgages, Phillips offered 41 slaves as collateral to secure a $23,000 loan.

Not uncommon at the time, and increasingly common during the antebellum era, one $23,000 mortgage was secured by 41 slaves. Woolsey Family Papers (MS 562), Box 69, Folder 26.

Though dubious, this in itself is not especially damning. Successful mortgages never see the security brought into question; instead, the debts are paid on time to the benefit of both parties. The Woolseys, an apologist might say, faced the same dilemma that investors face today: diversifying their portfolio across varied interests, even those that may cause controversy. In this sense, a mortgage secured with slaves was no different than an investment in shipping cotton. Slavery existed somewhere in the process, but there was little that William and George, as merchants and creditors, could do about it. Besides, their work with the manumission society, however faulty, demonstrated that their intentions were in the right place.

As their business dealings worsened, the Woolseys began to consider the possibility of actually acquiring the slaves as a security, and made plans to sell them. Woolsey Family Papers (MS 562), Box 69, Folder 27.

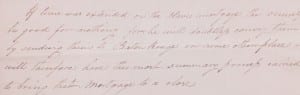

Yet the events that transpired removed any of these ambiguities. By 1807, Phillips proved to be overwhelmed in his new venture, and rumors came back to George that the debtor was unable to meet his upcoming financial obligations. Woolsey wasted no time in dispatching another agent to the New Orleans, with instructions to press the Woolseys’ claim with all haste to recover whatever funds might remain. He expressed his desire for the agent to avoid collecting the slaves as payment, but tellingly instructed his new agent to “dispose of them in the most summary way possible” in case nothing else could be collected. By 1808, Woolsey was actively pursuing their collection, before Phillips “[sent] them away to Baton Rouge” or another difficult to reach part of the territory. The Woolsey brothers, whatever their intentions at the outset might have been, had become slave owners and slave-sellers.

Ultimately, money trumped morals. Fearing that the slaves would be moved inland to Baton Rouge, Woolsey ordered his agent to collect them at once. Woolsey Family Papers (MS 562), Box 69, Folder 28.

Ultimately, this is meant neither to sensationalize the Woolsey family story, nor to insinuate that the accomplishments of the Woolsey family—and their works at Yale—are necessarily invalidated by this moment in two of their lives. A trove of much needed scholarship over the last decades has outlined the prominent roles northerners and northern institutions played in the trading and financing of enslaved people and the plantation goods they produced. A dozen years ago Craig Wilder’s Ebony and Ivy focused the issue on venerable academic institutions, and Yale continues to grapple with its past relationship with slavery and slaveholders to this day, as highlighted by the debate over the name of Calhoun College during the 2015-2016 academic year. Moral judgments on matters like this depend on more factors than could possibly be listed in this blog post.

Yet the facts of the case present us with a compelling historical case study that reminds us that American slavery was not confined to the plantation, and that though the heartless cruelties of the lash and the auction need to be remembered by all, they are far from the only instances in which slavery interacted with our society during the New Republic and antebellum years. The story of this pair of manumission-minded brothers from New York, who inadvertently acquired absolute control over the lives of 41 humans and sold them for cash rather than granting their freedom is a telling reminder that rather than a “peculiar institution” within American society, chattel slavery was a foundation upon which that entire society was built. The question is not whether the Woolseys could have absorbed the $23,000 loss that would have come with emancipating or manumitting their suddenly acquired slaves; for whatever it matters, their record books, which often reached six digits, suggest that it would have been a manageable loss. The right question should be how a society could exist in the Land of the Free that saw human beings enumerated, valued, and mortgaged as property, and how their otherwise liberal-minded new owners could wish for them to be quickly “disposed of” as though they were a sub-par shipment of any other commodity to be sold at whatever price could be salvaged. For while there are many rubrics for what constitutes a slave society, it’s difficult to think of one where this story, preserved in Yale’s Woolsey Family Papers, would not fit.

Note on quotations in this post that are not accompanied by an image of the quoted document: Quotations in this post relating to manumission and illicit trade with Cuba are taken from letters in the Woolsey Family Papers (MS 562), Manuscripts and Archives, Box 67, Folders 2-3. The discussion of the growing precariousness of George Phillips’ financial dealings in New Orleans are drawn from correspondence that can be found in the Woolsey Family Papers (MS 562), Box 68, Folders 11-12.