Decellularization Strategy Preserves Both Macro- and Micro-Structure of Porcine Heart Valves for Heart Valve Tissue Engineering

The four heart valves of the human body play a very important role in directing the blood circulating in the body. As the heart pumps blood from the right and left atria to the ventricles, the tricuspid and mitral valves open to allow blood through. Then they close to prevent blood from flowing back into the atria as the ventricles contract. Then, as the blood is pumped from the ventricles to the lungs and the rest of the body, the pulmonary and aortic valves open to allow blood through and later close to prevent backflow.

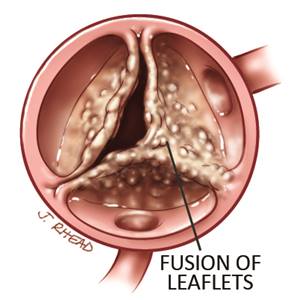

Many heart valves can be affected by various diseases. In valvular stenosis, valve leaflets may stiffen or fuse with other valves causing the opening to narrow. This is dangerous as it makes the heart have to work harder to pump blood and can lead to heart failure. Another condition is valvular insufficiency or regurgitation. This is when the heart valves do not close tightly and allow backflow of blood to occur. This disease forces the heart to pump harder to make up for the leaky valves, and less blood may be delivered to the rest of the body.

A cartoon visual of a diseased and fused heart valve leaflets. Fused heart valve leaflets restrict blood flow and force the heart to work harder.

Biomedical engineers have approached tissue engineering as one form of heart valve replacement. In this form of tissue engineering, whole valves to be used as replacement valves are first extracted from a donor and then decellularized to remove the donor cells. Often times, the donor of the valve is an animal, called a xenograft, so decellularization greatly reduces the immunogenicity of the valve, lowering the chance of an immune response in the recipient of the valve. These valves can also be reseeded which lowers the chance of calcification, so it is crucial that the microstructure of the valve is still there so cells can attach and proliferate.

As Prof. Gonzalez emphasized in class, the process of decellularizing tissues and organs is all about balance. The balance is between decellularizing enough to remove the cells while making sure to keep the valve’s structure and integrity intact. A proper valve replacement must meet both conditions- a valve with too much leftover cells may cause rejection, while a valve that gets decellularized to the point where structure becomes compromised may result in failure of the valve and the inability of cells to populate the valve.

As we learned, the three main types of decellularization are physical, biological, and chemical methods. Physical methods such as thermal shock or ultrasonic waves often are too harsh for valves, disrupting their structure. Biological methods involve enzymes or chelating agents and chemical methods help to remove cellular components. In this paper from the Haben group, the researchers test 3 different decellularization protocols for porcine pulmonary heart valves, using biological and chemical methods. The first method uses trypsin–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (TRP), the second method uses a combination of detergents and nucleases (DET + ENZ), and the third method uses a combination of an Accutase solution containing proteolytic and collagenolytic enzymes and nucleases (ACC + ENZ). The success of the decellularization is evaluated on the amount of remaining cellular content, the morphology of the decellularized heart valves, the extracellular matrix components, and the topography.

Compared with native valves as a control, HE staining showed that cells of the TRP group were incompletely removed, while DET + ENZ and ACC + ENZ groups showed no remains. After DET + ENZ treatment, the morphology of the valves were similar to that of native valves. Movat’s pentachrome staining showed that the ECM stayed intact with collagen and elastin. For the TRP and ACC + ENZ groups, the leaflets appeared enlarged and in the ACC + ENZ group, valve tissue structure was disorderly and compromised. Voerhoff van Gieson’s staining showed that all group preserved elastic fibers. Glycosaminoglycans is seen on native tissue, but in none of the three groups after decelluarization. Scanning electron microscopy showed that DET + ENZ treated valves maintained a matrix that was compact and unbroken. In contrast, TRP and ACC + ENZ treatments caused the matrix to dramatically change into a roughened surface or partially disintegrated.

Column A shows light images of native valves and valves decellularized by three different decellularization protocols. B shows HE staining revealing nuclei blue and matrix in pink. C shows Movat’s pentachrome staining revealing nuclei and elastin fibers in black and collagen in yellow.

Overall, it appears that DET + ENZ structure properly removes cellular content, while maintaining macro- and micro- structure, and most of the ECM components of the procine heart valve. In the future, I’d like to see how the valves mechanically perform in vivo. Decellularization of heart valves for the replacement of diseased valves requires the balance of cellular removal and preservation of structure and integrity that the DET + ENZ treatment promises.

Source: https://academic.oup.com/icvts/article/26/2/230/4372425