[Nota bene: With permission of its author, Jenifer Van Vleck, Assistant Professor of History at Yale University, we’re happy to post the following comments from a presentation made by Professor Van Vleck at a meeting of the University Library Council in the Manuscripts and Archives reading room on Friday, December 11, 2015. The focus of the meeting was on plans for renovations to Manuscripts and Archives, driven in part by the need for flexible teaching space within the security perimeter of the department.]

Archives as Passports

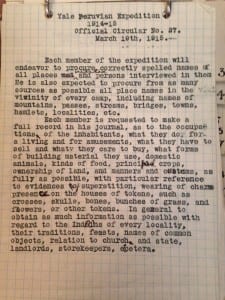

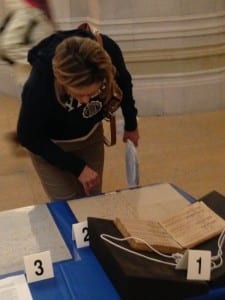

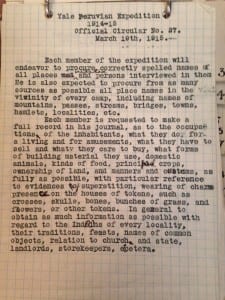

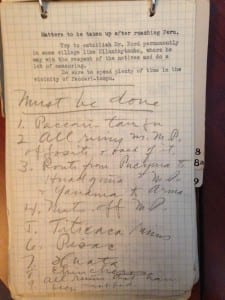

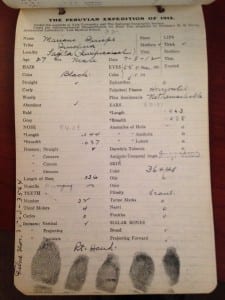

Hiram Bingham III, notebook of general orders, circulars, and reference notes, 1914-1915. Yale Peruvian Expedition Records (MS 664), Box 20, Folder 36.

The British novelist L.P. Hartley famously wrote, “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” To extend the metaphor, archives are the passport to that country. Special collections at Yale play a unique and vital role in allowing students to engage with the past—and, through their engagement with history, to think more critically and constructively about the present. Yale’s collections—particularly extensive in my own field, the history of U.S. foreign relations—offer students the opportunity to learn and practice the historian’s craft. In using these collections, students work with a rich variety of primary sources, including correspondence, diaries, oral histories, policy documents, organizational records, creative writing, photographs, and memorabilia. (And that is just a partial list!)

Hiram Bingham III, notebook of general orders, circulars, and reference notes, 1914-1915. Yale Peruvian Expedition Records (MS 664), Box 20, Folder 36.

While doing research in Yale’s special collections, students learn to reinterpret the lives and legacies of familiar historical figures—such as Charles Lindbergh or Eli Whitney, whose papers are housed at Manuscripts & Archives. However, they also meet new and sometimes unexpectedly fascinating characters—such as A.C. Gilbert, class of 1909. The creator of mid-20th-century America’s most popular toy, the erector set, Gilbert inspired literally millions of children to become interested in science and engineering. Today’s Yalies are unlikely to know Gilbert’s name or his historical significance—until they discover his papers here, as several students have done in my seminar on the history of technology.

Speaking of technology: Current and future Yale undergraduates are digital natives. They grew up with the Internet and email, and when they want to know something, they instinctively turn to Google or Wikipedia. This isn’t a bad thing, of course—Google and Wikipedia, among other online resources, are powerful tools. I use them every day. Yet, as I tell my students, Googling is a kind of “fast food” approach to research. You get to consume instant results, which can be satisfying but not always intellectually “nutritious.” And the word “consume” is fitting, I think, for we tend to skim Google search results quickly and selectively pick out what we want to find, usually from the first page or two of results. Archival research, by contrast, requires time and concentration. It’s not easy. It can lead to frustrating dead ends. Particularly when working with pre-20th century documents, it often requires reading nearly indecipherable handwriting. It requires careful attention to the contexts in which the contents of archives were produced, acquired, and organized. But, as my students discover, time spent in the archives, though at times challenging, is always intellectually rewarding. We sometimes don’t find what we expect to find. Yet we also find what we never even imagined to find. One of the greatest joys of my career is to witness my students becoming historians, and becoming excited about history through their archival research.

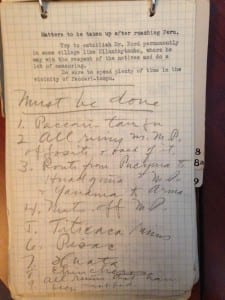

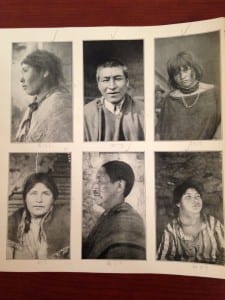

Dr. David F. Ford, photographs of Quichua individuals, 1915. Yale Peruvian Expedition Records (MS 664), Box 34, Folder 42.

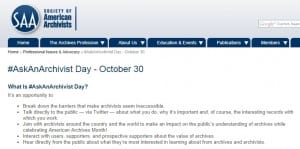

I teach students of all levels and academic interests: freshmen to Ph.D. candidates, STEM majors to history majors. In each of my courses, the resources of the Yale library—and Manuscripts and Archives in particular—are crucial to my teaching. I am immensely grateful to have the opportunity to collaborate with Yale archivists and librarians. Particularly because digitized archival databases are expanding so rapidly, it is difficult for professors to keep up with the latest developments and resources. In our own research, we rely upon librarians’ and archivists’ professional expertise in how to navigate the exciting yet often confounding and ever-changing landscape of archival resources. And we also rely on librarians and archivists in our teaching. Let me offer a few examples.

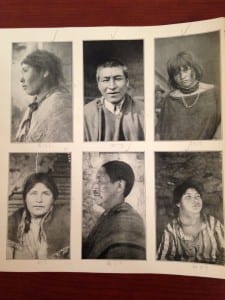

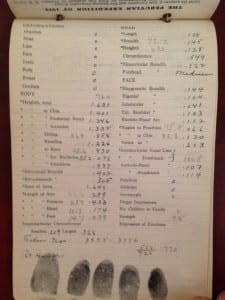

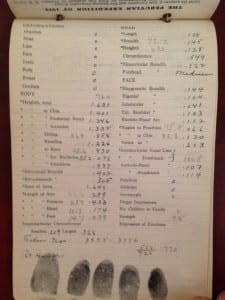

Dr. Luther T. Nelson, anatomical research notebook, containing records for individual native Peruvians, 1912. Yale Peruvian Expedition Records (MS 664), Box 20, Folder 28.

Freshman seminars. The History department, like many others, offers small seminars exclusively for freshman. These enable students to have frequent and substantive interaction with professors, and intellectual dialogue with their peers, at the very beginning of their Yale education. Last year, I co-taught a freshman seminar on U.S.-Latin American relations with History Ph.D. candidate Taylor Jardno, a specialist in Latin American history. Because our seminar was designed to introduce students to historical methodology as well as the particular topic, we required a research paper based on primary sources. Our students’ interactions with Yale’s archival collections was— according to their own evaluations of the course—an indisputable highlight of the semester. In collaboration with archivists Bill Landis and Maureen Callahan, we designed an interactive class session that focused on one particular Manuscripts and Archives collection: the Peruvian Expedition Papers, featuring Hiram Bingham, the famed Yale anthropologist and explorer whose expeditions to Peru in the early 20th century resulted in the rediscovery and excavation of the “lost” Inca city of Machu Picchu. (The swashbuckling professor, allegedly, is also the model, or at least a

model, for the character of Indiana Jones.)

Dr. Luther T. Nelson, anatomical research notebook, containing records for individual native Peruvians, 1912. Yale Peruvian Expedition Records (MS 664), Box 20, Folder 28.

Since most of our first-semester freshmen had not done archival research in high school, we thought that focusing on this one particular collection—which offers such rich and fascinating insights into the history of U.S.-Latin American relations—would be a manageable way to introduce them to the process of research and the types of materials that they can discover in archives. So my co-teacher and I went through the collection and selected records for our students to look at. We wanted them to understand the diverse kinds of materials one can find in an archive, even within a single collection. And we wanted them to think through how to work with different types of historical documents. How do you analyze a photograph, for example, as compared to diplomatic correspondence, or a legal contract? How do you place sources in dialogue with one another? What does any given primary source reveal—and what does it not reveal? What other types of sources would you need to consult in order to answer your research questions? We grouped our chosen materials into four categories: Bingham’s diaries; official reports from the expedition; photographs; and contracts—e.g. legal contracts between Yale and the Peruvian government that authorized Bingham to conduct archaeological work in Peru. After Maureen gave a brief presentation on the Peruvian collection and its history, students spent the rest of the class exploring the different materials. At first, they gravitated to what seemed to be the most exciting and accessible stuff: the photographs and diaries. The legal contracts, in comparison, seemed boring and difficult to interpret. Yet, as they spent time looking at and talking about the records, they gradually realized that these contracts were absolutely key to understanding the history of the expedition: how it came about, and what was at stake for Bingham, for Yale, and for Peru. “Dry” legal contracts came to life when read in conjunction—in conversation—with the other types of archival records. As I watched my students’ amazement and excitement as they handled, read, and talked about the Peruvian Expedition Papers, I realized I was witnessing a kind of meta-process of discovery: my students discovering history—and how to do history—as they encountered, first-hand, these documents on the discovery of Machu Picchu.

Upper-level seminars—“junior” now departmental seminars. I also teach upper-level seminars designed for junior and senior history majors. In each of these seminars, I dedicate one full class (two hours) to an instructional session here at the library, in which librarians and archivists offer a presentation on research methodologies and resources. One of my most popular seminars, “The Global 1960s,” examines the dramatic events of that decade in countries around the world. In order to introduce my students to relevant sources, Bill Landis and David Gary created a website with information about and links to library resources—both physical and digitized. During the third week of the semester, I bring my class to the library, where Bill and David lead a discussion about research methodologies: how to find and use online databases, for example. They also introduced students to particular collections relevant to the course. To that end, Bill and I identify about twenty relevant collections and placed boxes from those collections on reserve. I require students to explore these materials in advance of our library session, and to choose one particular box to discuss in class. For more advanced undergraduates, this interactive method of training them to work with archival materials has been highly effective in 1) ensuring that their final 15-20 page research papers are the product of intensive, semester-long work, not a stressful all-nighter before the deadline, and 2) getting them excited about the contents of archives. In the words of one student’s email to me: “I had so much fun digging through various boxes this afternoon. I eventually claimed the one containing the Asia Foundation’s reports in the late 50s and early 60s, although I also found President Brewster’s archive about coeducation at Yale quite fascinating. It was hard to choose!”

And it IS hard to choose! There is so much here. Using Manuscripts and Archives’ collections, my students have written seminar papers and senior essays on topics such as: U.S. governance of the Philippines during the late 19th and early 20th century. General Motors’ role in Germany during and after World War II. World’s fairs, from 1893 through 1964. The scholarly and political career of H. Stuart Hughes, one of the most prominent intellectuals of the 20th century. The Cuban Revolution. The creation of American football. The history of American conservatism. Yale’s role in promoting public health education in New Haven. The Yale-China Association. Gay, lesbian, and queer history, at Yale and beyond. One of the most fascinating research papers I’ve read, which this student ultimately turned into her senior essay, was about Christopher Phillips, Yale’s first out gay undergraduate, who lived much of his life as a cosmopolitan expatriate in nations throughout Asia and Europe.

My lecture courses are relatively large—on average, 150 students—so it would be impossible to hold an interactive class session at the library, as I do in my undergraduate and graduate seminars. However, in my lecture courses, I use the resources of Manuscripts and Archives in two ways. First, I encourage my Teaching Assistants to bring small groups of students to the library and familiarize them with its collections. Second, I incorporate Yale’s archives into my own lectures. My course “Origins of U.S. Global Power” surveys the history of U.S. foreign relations—and I say foreign “relations” rather than the more narrow term foreign “policy,” because while the course deeply examines the history of American diplomacy, it also features international interactions that are “informal” or not government-directed: such as business and trade, tourism, and cultural exchanges. Accordingly, while we analyze the legacies of presidents and secretaries of state, we also meet less-known people, who nonetheless had great impact on the United States’ international history. So, for example, while I use the Henry Stimson papers in my lectures on World War II (he was head of the War Department), I also draw upon the papers of Louise Bryant when I discuss American reactions to the Russian Revolution. Bryant, memorably portrayed by Diane Keaton in the 1981 movie Reds, was a prominent bohemian and journalist who was one of the few U.S. citizens to be in Russia at the time of the revolution. Her writings about it thus offer fascinating and unique firsthand perspectives.

The Yale Library, then, does not only offer a passport to the “foreign country” of the past. It offers a passport to the world. THANK YOU.