This is a guest post by Sarah L. Woodford, director of the Vincent Library at Saint Thomas More, the Catholic Chapel & Center at Yale University.

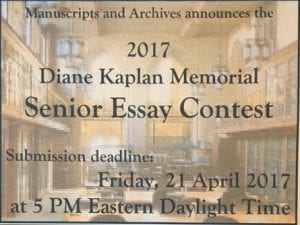

In his July 1983 article in The Catholic Historical Review Herbert Janick observes that Father Thomas Lawrason Riggs ’10, the first Catholic chaplain at Yale, was “both an intellectual respected for his secular accomplishments and a Catholic priest.” It then seems fitting that the two archives on campus that house his papers are Saint Thomas More, the Catholic Chapel & Center at Yale University and Yale’s Manuscripts and Archives in Sterling Memorial Library. Riggs bequeathed most of his personal and professional papers to the Saint Thomas More Corporation; but those papers and personal items, particularly pertaining to his bright college years, the immediate years afterwards, and his contributions to academic scholarship were donated to Manuscripts and Archives.

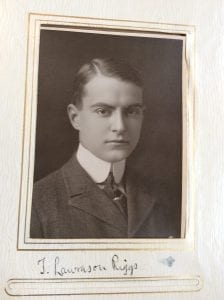

Photograph of T. Lawrason Riggs from Scroll and Key senior album, 1910. Call number: Yeg2 K61x 1910.

Born in 1888 to the Riggs banking family of Washington, D.C., Riggs was a graduating member of Yale University’s Class of 1910. While at university, Riggs studied English literature and French, Italian, Latin, and Greek. He was both a member of Scroll and Key and the Pundit Society, as well as the president of the Yale Dramatic Society (where he met his future roommate and musical theater collaborator, Cole Porter ’13). A renowned poet on campus, first as a contributor to the Yale Literary Magazine and then as the publication’s editor during his senior year, he penned the official class song for the class of 1910.

After Yale, Riggs pursued graduate work at Harvard University under the direction of Barrett Wendell. There he roomed with Dean Acheson ’15 (a future secretary of state in the administration of President Harry S. Truman) and Cole Porter (a future popular composer and entertainer), who were both pursuing law degrees. Neither Riggs nor Porter finished their Harvard degrees, instead they focused on the writing of See America First, a Broadway show financed by Riggs and pronounced a flop by New York critics in March 1916.

World War I brought Riggs back to the Yale. In the summer of 1917, months after the United States declared war on Germany, the twenty-nine-year-old joined The Yale Mobile Hospital Unit as a translator. After leaving the Yale Unit and gaining a foreign-language specialist position assigned to military intelligence in Paris, were he also acquired the rank of first lieutenant, Riggs decided to enter into the Catholic priesthood. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1922 and after a trip to Europe to consult with the Catholic chaplains at Cambridge and Oxford, took up residency at Yale.

One of the “designs” Riggs bequeathed to Saint Thomas More, the Catholic Chapel & Center at Yale University, circa 1938. The Fr. Riggs Papers, Saint Thomas More.

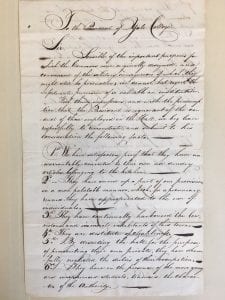

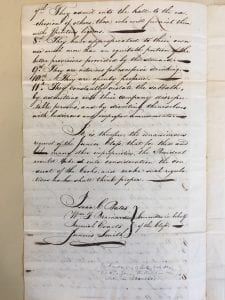

Riggs spent his tenure as Catholic chaplain entertaining young Catholic creatives at his lavish home on Whitney Avenue, building what is now Saint Thomas More Chapel, and pursuing a book project about Joan of Arc. His book Saving Angel: The Truth about Joan of Arc and the Church, was published posthumously in 1944 by The Bruce Publishing Company of Milwaukee. Riggs died unexpectedly of a heart attack on April 26, 1943. He was fifty-five. In his will, drawn up in November 1938, he bequeathed all his “papers, books, correspondence, records and designs” that concern or have to do with Saint Thomas More, to the Saint Thomas More Corporation. All other papers, books, and correspondence that did not interest the Corporation, were to go to Sterling Memorial Library at Yale University.

Among the items Riggs bequeathed to Manuscripts and Archives were two Scroll and Key senior albums, from 1909 and 1910. The former from his brother, Francis, who graduated the year before him, and the latter from Riggs’s senior year. Both albums are leather-bound and contain black and white photos of the society’s senior members with their signatures underneath. Riggs’s 1910 album also contains a snapshot of the secret society’s ivy-covered tomb in the album’s last frame.

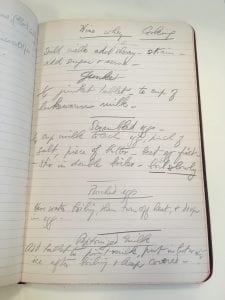

Recipes to prepare for injured soldiers, part of Riggs’s training for the Yale Mobile Hospital Unit, 1917. Thomas Lawrason Riggs Papers (MS 704), Box 1, Folder 9. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

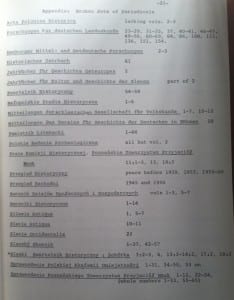

Riggs also donated a collection of his notes and papers that now make up the Riggs Papers. Items of note include his typed manuscript of Saving Angel and a notebook from 1917 that contains notes from his training for the Yale Mobile Hospital Unit. The notebook is blank in the middle and its back portion contains notes in pencil dated July 18-21. These notes instruct on how to identify contagious diseases, bandage various sprains, set broken bones, and prepare meals for the injured (poached eggs and cocoa are two items on the menu). There is also a particularly sobering section that describes the different sorts of poisonous gas a soldier could inhale, how to identify them, and which ones would prove fatal.

As Saint Thomas More, the Catholic Chapel & Center at Yale University celebrates eighty years in October 2018, the community once more considers its beginnings and the priest at the center of those beginnings. Riggs was a chaplain and a Yale man—how appropriate that like his life, the archives that continue to keep his memory reflect this as well.