This is a guest post by Robin Dougherty, librarian for Middle East Studies at the Near East Collection,Yale University Library.

The year 2016 marks the 175th anniversary of the appointment of Edward Elbridge Salisbury (1814-1901) as Professor of Arabic and Sanskrit Languages and Literatures at Yale. An exhibit devoted to exploring this groundbreaking appointment, its context, and its legacy (and based upon materials in Yale’s Manuscripts and Archives department, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, and general library collections), is on display in the Memorabilia Room of Sterling Memorial Library through February 6, 2017. If you had the time, you too could trace Salisbury’s life and legacy through documents held in Yale collections and elsewhere. For the Christmas season, I’d like to highlight two paragraphs that can be found in items held in the collections of Manuscripts and Archives.

Salisbury (B.A. 1832), scion of the wealthy Salisbury family of Massachusetts, married his cousin Abigail Phillips (1814-1869) shortly after completing his theological education at Yale. The two then set out on the customary honeymoon/”Grand Tour” of Europe. As Salisbury later wrote in his brief autobiography, “We younglings … were amply provided for, and could follow freely our fancies and tastes.” On this Grand Tour, Salisbury not only visited the great universities of Europe, meeting the greatest living scholars of the time, but stayed on long enough in Paris and Berlin to acquire a foundational education in Oriental languages (principally Arabic and Sanskrit), aiming to establish himself as an academic (and, in 1841, successfully obtaining a Yale professorship to teach these two Oriental languages). He was among only a few dozen Americans up to that point to make the arduous journey across the Atlantic in pursuit of advanced study in Europe—a group dominated by graduates of Harvard and Yale. His journal entries and the letters that he and Abby wrote back home reveal their discoveries and their impressions as New England innocents abroad.

Although terribly homesick for her family, friends, and her Congregationalist church back in the United States, newlywed Abby gamely explored Europe with her husband Edward, studying European languages with him and giving birth to their daughter Mary (1837-1875) in Switzerland. In December 1838, not long after arriving in Berlin with Edward and little Mary, Abby described to her mother-in-law Abigail Breese Salisbury, with great excitement, a scene utterly unfamiliar to most New Englanders of the time:

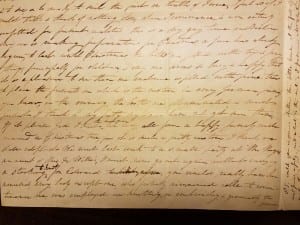

Letter from Abigail Phillips Salisbury to her mother-in-law Abigail Breese Salisbury, 16 December 1838. E.E. Salisbury Papers (MS 429), Box 11, folder 45a. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

This is a very gay time in Berlin, every one is making preparations for Christmas, a fair has already begun, to last until Christmas, the booths are filled with toys & fancy things, principally for children, & every one seems so busy & happy that it is a pleasure to see them, one enclosure is filled with pine trees to place the presents on, which is the custom in every German family you know, in the evening the booths are illuminated & must present I think a very pretty sight. [Salisbury Family Papers (MS 429), Series III, Box 11, Folder 45b, APS to ABS, 16 December 1838.]

She concludes her letter to her mother-in-law with the fervent hope of establishing the “pretty” German-style observation of Christmas in her own New Haven home after returning from the Grand Tour. Theodore Woolsey, future president of Yale but at that time still just a professor of Greek, was Salisbury’s brother-in-law, having married Salisbury’s sister Martha—Abby’s 1838 letter paints a lovely picture of her own little family joining Madame Salisbury along with Woolsey’s budding family in a style of Christmas celebration that would be utterly innovative in New Haven:

If it please God, I trust the next year we may all form a happy family circle around a Christmas tree, for it is such a pretty custom, I think we shall adopt it.

In his journal entry for Dec. 18, 1838, Edward recorded his own impressions of his first experience of the celebration of Christmas, German-style:

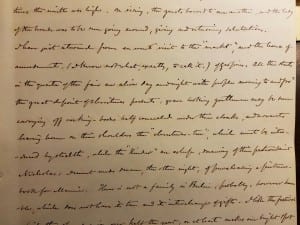

“Journal of travels in Europe 1838 May 27-1839 Aug 6,” p. 147. E.E. Salisbury Papers (MS 429), Box 5, folder 251. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

I have just returned from an eveng visit to the “markt”…. All the streets in the quarter of the fair are alive day and night with people moving to and fro’ the great deposit of Christmas presents; grave looking gentlemen may be seen carrying off rocking-horses half concealed under their cloaks, and servants bearing home on their shoulders the “Christmas-tree,” which must be introduced by stealth, while the “Kinder” are asleep, dreaming of their patron Saint Nicholas…. There is not a family in Berlin, probably, however humble, which does not have its tree and its interchange of gifts.–The house of amusement, as I style it, exhibits dioramas, green-houses, a saloon for refreshments, (where are made tables for separate parties,) and a mock concert of automaton musicians,–a capital quiz! From one of these dervish objects to another, old & young, high and low stroll, and look and laugh, and look and stroll again. It would seem as if the whole city had given up its cares and were in quest of wherewithal to divert the mind. Almost every face looks brightened and intent,–miserable must he be who has not some share of the general blitheness. [Salisbury Family Papers (MS 429), Series I, Box 5, Folder 251: “Journal of travels in Europe 1838 May 27-1839 Aug 6,” p. 147-148. Salisbury here has translated the German word “Festhalle” as “house of amusement.” He uses “quiz” to mean a practical joke or hoax of some kind. His use of “dervish objects” is unclear, perhaps referring to the spinning and gyrating movement of the automaton figures.]

Edward was a connoisseur of the arts, and throughout his journals and letters freely offered his opinions on the musical offerings of the day. As part of his journal entry quoted above, he made this interesting suggestion

I like the festival which thus spreads a joy over half the year, or at least makes one bright spot when, otherwise, all would perhaps be gloom, or dimness; I could suggest, as an addition, however, that there might be some great musical festival on this occasion, to give utterance to the deeper feelings associated with the season in the performance of the “Messiah”. I think it is not preaching which one wants at such a time.

Handel’s “Messiah,” originally composed for use during Lent, had been popular in the U.S. and Europe since its composition. It was first performed on Christmas Day, in its entirety, in Boston, 1818, but did not achieve its current popularity as a piece for the Christmas season until the late 19th century–Salisbury’s taste was way ahead of its time!