Frida was my favorite film of the semester and after learning of Harvey’s involvement, I questioned my feelings. I originally thought the work felt international and authentic to Frida’s Mexican heritage. I initially ascribed these feelings to the abnormal amount of sexuality displayed. Unlike many American-made films, Frida includes so much normalized sexuality that it feels different from many American-made films that capitalize on gratuitous sex scenes. However, after reading Salma Hayek’s New York Times Op-Ed and rewatching several scenes, I realized that while the sex scenes certainly support a less “American” vibe, the music and scenery choices define its distinctness. While it’s typical for movies to be shot on location, it’s often rare for the traditional music of that region to accompany the scene. Film composers often mix a regions traditional music with the normalized Hollywood production sound (big drums, low strings, complex sound design, etc). In Frida, however, the Mexican scenes feature authentic mariachi music, Latin jazz, and vocal standards; the New York City scenes include Duke Ellington-style big band tunes; and the Trotsky scenes include, perhaps incidentally, traditional 19th-century European string writing (typical in Hollywood music and related to Russian music). Because I’m sensitive to how movies are scored, I think the music helped me appreciate the work and certainly accented the distinct Mexican culture from which she originated and the contrasting cultures with which she conflicted throughout her life. Even though Weinstein produced Frida, I will still watch and appreciate the score of this movie and Hayek’s success breathing life into Kahlo’s story.

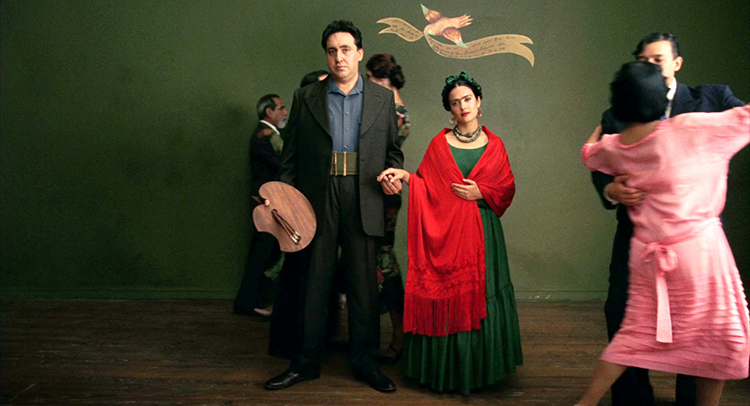

Note the music notes at the top of her painting.